Name: Todd Dillard

Hometown: Houston, TX

Current City: Philadelphia, PA

Occupation: Writer and Editor at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

Age: 35

What does poetry mean to you?

Before I describe what poetry means to me, I feel I should first establish what I think poetry is. Poetry is a form of entertainment that uses precise language (and images) alongside elements of musicality, such as rhythm and timbre. I recently read something that resonated with me too (I think originally said by Jericho Brown at this year’s AWP conference) about how a poem must be written towards mystery, and I completely agree: first, because it conjures up an idea that what is central to a poem must be revealed; second, because it notes a poem must possess movement. I think balancing clarity and inventive language with mystery, metaphor, and movement is the poet’s greatest struggle. Lean too far towards clarity, and the poem is prosaic. Lean too far towards mystery, and it’s effusive gibberish. Stay in one place (i.e., choose not to move), and the poem becomes transactional, episodic, journalistic even. Do all of these things, but fail to write something entertaining too—and, well, who cares!

It’s in balancing these elements that I find poetry’s meaning: poetry, to me, is connectivity. It’s a collaboration between poet and audience to erect a bridge made out of language that links something known or possible to the unknown or impossible. It means writing or reading something that is larger than itself; there is a moreness to poetry, an additional dimension or multiple dimensions that only through the poem we can glimpse. This is why I started with my definition: absent the things noted above, a poem fails to connect, we lose sight of what exists beyond the poem, and the art of the poem becomes meaningless or impenetrable. A poem that fails to connect can only be a polished draft, a hollow gesture.

Favorite Book of Poetry: The World Doesn’t End by Charles Simic

The World Doesn’t End by Charles Simic is the book of poetry I have read the most, and lost the most, and given away the most, and purchased the most, which I suspect makes it my favorite book of poetry. (I currently own two copies: a mint-condition one I can give to friends or read at leisure, and a crinkly one I don’t mind reading in the rain.) These compact poems have within them everything I love about poetry: beautiful language, music, mystery, clear stories, stunning images, and depths that over my many readings I have yet to fully pierce. I will spend a lifetime returning to these words, and may never fully grasp their meaning. As a lover of language and mystery, this is pure delight.

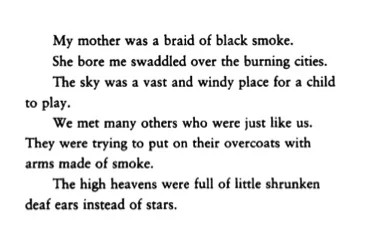

From "My Mother was a braid of black smoke..." by Charles Simic

Why do you like “My mother was a braid of black smoke…”?

I chose the first poem of this collection because it is perfect. Its structure is so fable-like, with its breath-long sentences and matter-of-fact tone cleaved to fabulist images. It’s only when you learn about Simic and how he spent much of his childhood surviving World War II that the horror of the final line strikes you—the desperation to turn to the sky and scream for help, the terror of encountering the stars’ deafness. This terror then kicks up into the rest of the poem like river silt: the burning cities, the dead “many others,” the mother as a “black braid of smoke.” Simic here has achieved the impossible, lulling us with a false fable, giving us something paradoxically simple and sinister, writing text that is combustible, but only when we are already cradling it in our hands, our mouths, our eyes. All 64 words of this poem reach through my skin to touch my bones.